The Early Days & the Republic

The early days of Rome remains a matter of uncertainty. "Almost no Greek writer mentions Rome before 300 BC, and no native historian before 200 BC. By the time these histories were written, Rome was already a dominant power within Italy."1 Most of what we know of the early dates come from later historians—principally Virgil and Livy—who lived many centuries after the events and it is difficult to tell how much of this history is reliable and how much are myths and legends.

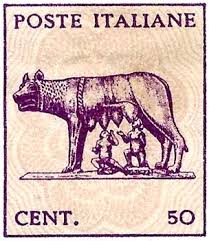

Roman traditions tell that their city was founded on the banks of the river Tiber by Romulus at a date that corresponds to 753 BC of our calendar. The traditions contain two strands of material, often woven together in different permutations of details. The first speaks of the arrival of Aeneas and his troops from Troy and their capture of the Latin plain in the 12th Cent BC. The second strand tells of a princess descendant of Aeneas who became pregnant by an unnamed man (some say he was Mars, the god of war) and gave birth to a set of twins, Romulus and Remus. Rejected by her father, the twins were exposed to death but was found and brought up by a she-wolf. A quarrel broke out between the two brothers while they were deciding on where to site their own city (Romulus for the Palatine hill and Remus for the Aventine) in which Remus was killed. The city thus became Rome, the city of Romulus.

The city was ruled at first by kings, eight of them, who became increasing tyrannical until the last of them, Tarquin, was driven out in 509 BC and the city-state refounded as a republic.

From City-State to Super-Power

Though dominated by a few powerful families who filled the offices of magistrates and the Senate, the Republic was remembered in later times as an age of liberty and prosperity. This was also the age when Rome was transformed from a small city-state into a major power in the ancient Mediterranean world, beginning about 500 BC when she began to assert and extend her influence and hegemony towards other Italian cities. Two centuries later her influence was felt almost across the entire Italian peninsula, and her colonies occupying strategic positons in the Apennines and the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic coasts; this despite a short setback when Rome was captured by the Gauls in 390.

Rome's success and ambitions soon attracted the attention of other powers in the region. One of these was King Pyrrhus of Epicus, who was not himself unambitious. One of the Italian cities on the Adriatic coast that was beginning to feel the breathe of Rome's appetite was Taranto, which was formerly an ally of King Pyrrhus, and now turned to him for help. Beginning in 281, King Pyrrhus made a number of attempts to invade Italy. The invasion ended in the defeat of the Romans in a number of battles but the expression "a Pyrrhic victory" entered into our common vocabulary as an idiom for a victory won at too high a price. Forced to cut his losses King Pyrrhus retreated to Epicus in 275, where he was to die three years later in battle against the Macedonians. The war with Pyrrhus, however, brought Rome to the attention of the Greeks, with two important consequences. Firstly, from now on Roman history began to find firmer and more evidentially-founded treatments in their more decidedly literary and rational hands. Secondly, it also became clear to everyone across the Mediterranean world that Rome was now a force to be reckoned with; soon diplomatic emissaries and appeals for help, especially military, followed. This—together with growing Roman belligerence—naturally brought Rome into disagreements with other parties and inevitably, into other wars. The most serious was with her former ally, the city of Carthage in North Africa, when their spheres of influence clashed. The First Punic War2—largely a naval affair fought around the Tyrrhenian Sea—was fought over who should possess Sicily; it was ceded to Rome when Carthage sued for peace in 241 BC.

Roman soon siezed Sardinia in the west and then Corsica. Carthage, meanwhile, had established a new empire in Spain, centered around Cartegena (Carthago Nova, "new Carthage"). Spain, with her silver mines, soon caught the attention of Rome, and the Second Punic War broke out in 219/8 BC. Hannibal led his armies across the Alps into Italy, and in 216 dealt Rome her most desastrous defeat at Cannae; some 60,000 Roman soldiers died at the cost of some 6,000 Carthaginians. Far from home, and stretched on supplies and reinforcement, Hannibal failed to take Rome, and was forced eventually to retreat. Rome, however, took the war to Africa and General Publius Cornelius Scipio soundly defeated Hannibal at Zama in 202. For this Scipio was nicknamed "Africanus."

Just two years after the defeat of Hannibal, Roman armies, on the request for help from that Aetolians.3 The Aetolians' unhappiness with their share of the success, however, would open the door for the Roman march into the east. While all these were happening in the west, Antiochus III of Syria had been attempting to extend his control westward and had even managed to secure a toehold in Thrace. Now, in alliance with Aetolia, he crossed into Greece. The responce of Rome was swift; soundly defeated at Thermopylae in 191, Antiochus retreated into Asia Minor (modern Turkey), pursued by Consul Scipio, the brother of Africanus. Defeated again at the battle of Magnesia, Antiochus signed the Peace of Apamea in 188, renounced all claims to the territory of Asia Minor (modern Turkey), and earned Africanus' brother the nickname "Asiaticus."

By this time almost every facet of Mediterranean politics took their reference from Rome. Soon most of Greece came under Roman control. And when, in 168, Antiochus IV Epiphanes tried to invade Egypt, he was met by his old friend the Roman envoy Popilius Laenas just outside Alexandria who ordered him to turn around home. Antiochus asked for time to seek counsel with his advisors, upon which Laenas drew a circle in the sand around the king and said, "As long as you give me an answer to take back to the Senate before you leave the circle."4 Whether the incident actually happened as told, the fact of the story reflects the power and influence of Rome across the Mediterranean world in the middle of the 2nd Cent BC.

In 146, war broke out between Rome and the Achaeans. To make a show of her powers, Rome sacked the city of Corinth, "its treasures plundered by Mummius, and given to his soldiers and as rewards to allied communities, and the city . . . was abolished. This was an atrocity not seen in the Greek world since Alexander the Great had destroyed the city of Thebes as a symbol of what he could do if he wished."5 The same year, Rome decided it was time to end the hostilities with Carthage. In the 'Third Punic War,' her armies stormed and captured Carthage. The city's survivors were sold off as slaves and the city demolished. "The Carthaginian language was eventually lost and only the writings of later historians shed any light on Carthage's military institutions and its most famous general, Hannibal."6

No one living in the Mediterranean could not have been appalled by the destruction of these two glorious cities and recognized that their own nations had been put on notice. At the same time, however, things were going awry for Rome. The reasons are complex, but among them we can recognize first the fact that while she was a master at hegemony, Rome had no consistent policy with what to do about her conquered territory. Though the spoils of war was great and enriched the city of Rome, the territories were often were turned over to allies, who then used their friendship with Rome to build up their own powers and later to turn on Rome. In the 19th Cent, the Victorian historian, J. R. Seeley, would speak of the British Empire as having conquered and peopled the world "in a fit of absence of mind."7 In this "absence of mind," the Romans slipped into empire, preceeding the British by seventeen centuries. But as it reshaped the outside world to its own benefits, the Romans were also—even more absent-mindedly—changing, and it would put the Republic, and all the ideals that it represented, in jeopardy.

Low Chai Hok, ©Alberith, 2019