Co-originator with Alfred Russel Wallace (who for too long was ignored though there is now a movement to give him the credit due to him) as the founder of the theory of biological evolution by natural selection.

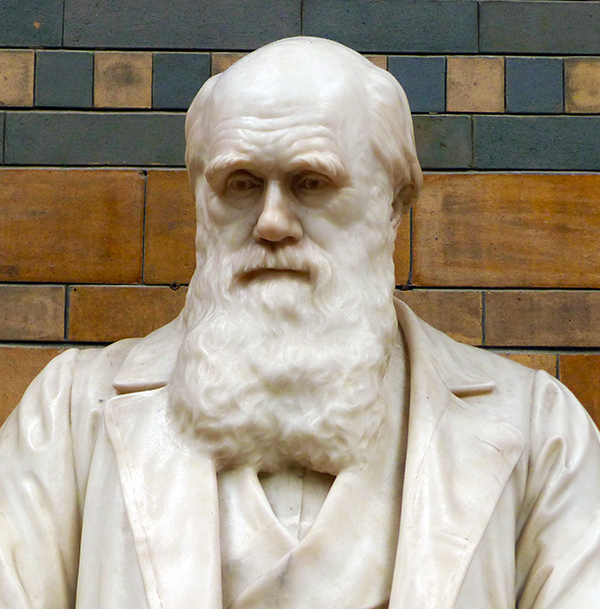

Statue of Darwin at the Natural History Museum, London.

Charles Darwin was born to a wealthy Shrewbury doctor, which allowed him to waste most of his early life, first as a medical student in the University of Edinburgh, and then at Cambridge. He would have been destined for life as a country parson until an opportunity came in 1831—through his friendship with Rev. John Henslow, professor of botany at Cambridge–to sail as a gentleman companion on HMS Beagle on hydrographic survey to South America, and then a series of chronometrical soundings around the world. Darwin's interest in natural history quickly made him the de facto naturalist on board (the ship doctor was the official naturalist who was, nonetheless, happy for the young man to assume the role), and he began to amass a huge collection of animal and plant collections as well as to make geological and biological observations on the voyage. His report and publication of The Voyage of the Beagle made him famous. As his collections were being sorted out and properly identified and he began ponder on the significance of what he had observed. Stimulated by such writings of Rev. Thomas Malthus (Essays on the Principle of Populations) and Charles Lyell (Principles of Geology), he began his first notebook in 1838 about the possibility of an evolutionary explanation (what he termed 'transmutation') based on emperical observations rather than the many fanciful theories that had already been published (including one by his grandfather).

Darwin married his cousin, Emma Wedgwood, settled down, had children, and worked on many projects, including, famously, pigeon breeding. He continued to tinker with his evolutionary idea but refused to publish anything on the matter for two decades, despite the urgings of his close friends like botanist Joseph Hooker and geologist Sir Charles Lyell (his procrastination remains a matter of debate). Then one fateful day in June 1858 Darwin received in his mail a paper from Alfred Russell Wallace, a younger naturalist with whom he had been in correspondence for some time and who was then out collecting in the Malay Archipelago (Indonesia). Wallace had asked Darwin to read his paper and, if he thought it any good, to convey it to Sir Charles Lyell (Wallace's letter is not preserved; the thought of passing it on to Lyell may have its publication in mind, since Lyell would have been a capable mover in such matters, though Darwin denied this). Darwin was shocked, for Wallace had beaten him to a theory of the origin of species that "if Wallace had my MS sketch written out in 1842, he could not have made a better short abstract! Even his terms now stand as heads of my chapters." In the end, Darwin was not forestalled in fame; Lyell and Hooker arranged—without Wallace's permission (he was not important enough a scientist to consult)—to have an abstract of the theory Darwin had written out in in 1844 and Wallace's paper read (with precedence given to Darwin) at a meeting of the Linnean Society of London on 1 July, 1858 (Darwin was absent attending to the funeral of his son who had just died; Wallace was thousands of miles on the other side of the world and oblivious of any of these things).

The following year, Darwin published his now famous book, On the Origin of Species, a fuller (though he still felt it not full enough) exposition of his theory of evolution by natural selection. The book sparked a great deal of debates—both in favour and in criticism, and generating a great deal of heat that still felt today—but it made Darwin's name synonymous with evolution. Darwin, always shying from public, was happy to allow his friends—Hooker, Lyell, and especially Thomas Huxley—to fight his public battles on his theory's behalf; he continued indulging in his various projects and continued to publish. He died in 1882, after a series of heart-attacks and—with the machinations of his friends—was buried at Westminster Abbey, a short distance from where Isaac Newton laid in rest.

Further Reading & Resources:

☰ Debating Darwin: How Christians responded. Christian History Issue 107 (2013).

☰ Nigel Scotland, "Darwin and doubt and the response of the Victorian churches," Churchman 100.4 (1986): 293-308. pdf

☰ David N. Livingstone, "The Myth of Darwin's Metaphor," Journal of the Irish Christian Study Centre 1 (1983): 35-47.

©ALBERITH

030919lch