Hong Xiu Quan (or Hung Hsiu-ch'uan in older works) was founder of the Taiping Tianguo, the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace, a society with a puritanical and authoritarian ideology based on a selective reading of the Bible which eventually turned into a violent military movement that swept across the heartland of China believing that it was called to demolish the demonic Qing dynasty. Its most explosive phase, played out mainly in the capital city of Nanjing, from 1851-64, became known as the Taiping Rebellion. All in it took about 20 million lives, making it the most destructive civil war in world history.

Hong Huo Xiu (Chinese surnames always come first) was born to poor peasant parents of the Hakka dialect in Guangxi province. This did not stop him from the dream of becoming one day an official of the Qing administration; it was, after all, every young man's dream and hope of escaping from the proverbial poverty of every Han Chinese. Once, he failed the compulsory imperial examination for qualification for such a post and fell into despondence and illness during which he have a vision in which he was lifted into the heavenly realm and he saw an elderly man with a golden beard, like a foreigner, seated on a throne. Beside him was a younger man who was introduced to him as his elder brother. The old man moaned about the state of the world and how humanity had abandoned themselves to demon worship. He commanded Hong that it was his duty to destroy the demons and turned the world to right. He also gave Hong a new name, Hong Xiu Quan. When he woke, Hong changed his name but did nothing else about his vision.

In 1843 Hong sat for the exams a fourth time but failed again. As, in anger, he railed against the imperial system for what he saw as its injustice and corruption, the vision came back to him. Piecing the puzzle of the vision with what he had read in a tract given to him by an American missionary years ago, he began to realize that the elder man was God, the younger man introduced to him as his elder brother was Jesus, and his mission in life was to destroy the demonic power that was the ruling imperial powers. He, with his cousin, got baptized and began to preach and to attack idols and shrines everywhere they went. Hong was a powerful preacher, his vision was compelling, and the fact that he seemed protected from harm by the demons made a powerful impact on his audience. By 1850 he had a following some twenty thousand strong, which he called the God Worshipping Society.

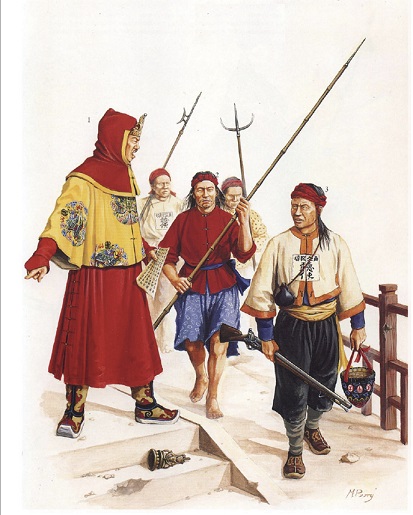

Soldiers of the Taiping Tianquo

As the movement grew so did his pride and view of his own mission, and from a purely spiritual motive, the movement became increasing civil and political; he the destruction of the Qing dynasty—a foreign and demonic imperialist institution—as his calling. On the first day of 1851 the first clash between his followers and the imperial army occurred; the small government army sent to check on them was slaughtered. In the wake of this victory Hong proclaimed the Taiping Tianguo (the Heavenly Kingdom of Great/Eternal Peace) and he was crowned Heavenly King. Then began the march on the imperial capital and—justifying the action on the basis of what he had read in the book of Joshua—with great slaughter along the way as those who refused to give up their traditional way of life were considered demonic followers. In 1853 they siezed the ancient imperial capital of Nanjing (in the province of Anhui), which they then turned into their New Jerusalem. There they stalled; the army of thirty thousand they sent north to take Beijing was checked by imperial forces in Tianjin, less than seventy miles from their goal. Were they able to march on to Beijing, Chinese history today would read very differently today.

The Qing administration had earlier thought of the movement as little more than a local disturbance. They were also distracted by the European powers who were then demanding—and to underscore their determination Anglo-French forces had destroyed the Yuanmingyuan in 1560) another round of the unequal treaties that had become the hallmark of the history of the Fanqui (foreign devils) in China. Once they had gotten their deals, the Western powers were happy enough to step in and help the Qing army put down the Taipings. (One of the more famous of those generals who participated in the effort was Charles Gordon, a devout Christian with a bizarre theology and who, recuperating from his efforts afterwards in Jerusalem, found a tomb near an outcrop that looked—to him—like a skull and decided that it has to be the tomb of Jesus; it is today known as the Garden Tomb.) The end came in 1564 when, riven by starvation and internal divisions, Hong Xiu Quan died (either assassinated or committed suicide). By then at least twenty million persons had paid for his adventure with their lives; far more, proportionately, than those who died in the contemporary American Civil War (1861-5 with about 800,000 lives lost).

The impact of the Taiping Rebellion on Christianity in China is difficult to gauge. It is hardly remembered among common Chinese folks as detrimental to their attitudes towards the Christian faith. One possible reason was that the movement—though attracting some initial attention from foreign missionaries at the time—was entirely an indigenous. Its ideology also had enough of an anti-foreigner element in it to be accorded some recognition as a patriotic movement. As one American said of George Bush, "We know he is a bastard, but he is our bastard." So was Hong Xiu Quan "our bastard" as far as the Chinese was concerned.

In light of the stupedous event that it was, it sounds pedantic to ask if there a moral lesson here for us lay-preachers? If we take nothing else away let it remind us of the need to preach the gospel whole and soundly. We never know what our audience take away from us and what they can do with them.

Further Reading & Resources:

Alec Ryrie, Protestantism. London: WillianCollins, 2017. See esp. pp391-424.

Jonathan D. Spence, God's Chinese Son. The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996.

(The definitive literature on the subject is naturally in Chinese; probably the multi-volumed Taiping Tianguo yinshu.)

©ALBERITH

110321lch