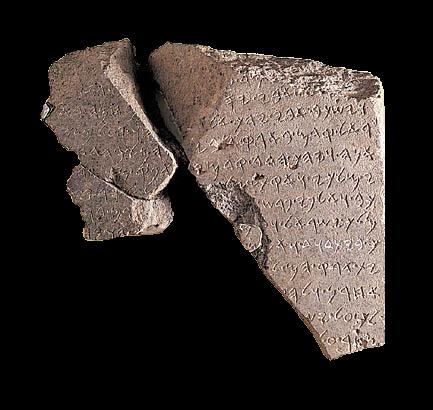

To say that King David was a central figure in the Bible is to make the most undisguised understatement. He was the founder of the dynasty that ruled Judah for half a millenium, and from which the messiah descended. Yet archaeological remains from David's empire are scarce, and extra-biblical references to King David non-existent until the accidental find of a fragment of a stele in Tel Dan (in northern Galilee) in 1993.

The discovery of the Tel Dan Stele fragment remains one of the most amazingly fortuitous events in the history of archaeology.

Tel Dan is the site of the ancient city of Dan. It is located at the foot of the Mount Hermon mountains, a few kilometers west of the source of the Jordan River. Archaeological excavations at the site began in 1966, and have continued almost without interruption ever since. Hershel Shanks, Editor of Biblical Archaeological Review, tells the story of how Gila Cook found the fragment on 21 July 1993:

Gila herself does not actually excavate. She draws and measures what the team has excavated. But she was not even drawing or measuring when she discovered the inscription. And it was not even during the excavation season. Avraham Biran, the dig director, was driving up from Jerusalem to show the site to a visitor. Gila had some surveying work to finish, so she asked if she could go along with Biran. At the time—1993—the distinguished, universally admired archaeologist was 83. Today he is 95 and has retired. Gila always refers to him as Dr. Biran.

While Biran showed the visitor the site, Gila went about her unfinished measuring. She brought her surveying equipment with her. Her level, set on a tripod was bulky, especially with the other equipment and boards she was carrying.

Biran finished showing the site to the visitor, who then left in his own car. Biran called for Gila to gather her equipment and come down the hill to get into the car for the return trip to Jerusalem. As she walked down, she stopped to rearrange her load, placing the level and tripod on a large stone of a recently excavated ancient wall. . . .

It was that accident—placing the level and tripod on the wall—that was the stroke of fortune, enabling her to notice the inscribed stone within the wall as she picked up her equipment.

She was stunned. Her instant reaction was to call to Biran: "Bo," she yelled. It was the curt Hebrew instruction to kids to come. It was not even the more polite "Bo-na"—Come, please. No "Dr. Biran" this time.

Biran came running. Gila pointed to the letters. Biran, a native Israeli going back three generations whose first language is Hebrew, looked down and exclaimed in English, "Oh, my God!"

And so the Tel Dan "House of David" inscription was discovered. Shortly thereafter, it was on the front page of the New York Times.

H. Shank, "Happy Accident: David Inscription," Biblical Archaeological Review 31/5 (Sept/Oct 2005) 46.

This discovery sparked a renewed search for the rest of the stele; two smaller pieces were found the following year. Together they represent the first extra-biblical evidence for the existence of King David.

The stele has since been dated to the 9th Cent BC, within a century of the split of the kingdom into Israel and Judah. Assuming that the two main fragments found fit together as in the photograph, the inscription contains portions of thirteen lines, of which a translation would read (texts in square brackets are conjectural reconstructions):

. . . my father lay down [died], he went to . . . the king of Israel previously campaigned in the land of Abil [or "land of my father"]. [The god] Hadad made me king, me. And Hadad went in front of me . . . of my kingdom. And I killed two powerful kings who harnessed thousands of chariots and thousands of horsemen. [I killed Jeho]ram, son of . . . king of Israel and I killed [Ahaz]iah [his] son . . . of the house of David and I laid . . . their land . . .

If this translation represents a correct reading of the fragments as they appeared in the original stele, we can make the following observations:

1. The stele was erected most likely by a Syrian king on account of his reference to Hadad, the Aramic deity.

2. The portion of text available opens with a statement that Israel had previously encoached his father's territory ("Abil" or "land of my father").

3. He then boasts of having been made king by Hadad and granted victories by it ("Hadad went in front of me").

4. He further boasts of having killed two kings, possibly one of Israel and the other of "the house of David."

These are what can be said with certainty. Everything else claimed by scholars, it must be remembered, are conjectures and interpretations based on any number of factors and bias brought into the inscription. A host of literature on the stele and inscription have appeared in the years since its discoveries. Among some of the more widely accepted interpretations we may cite the following:

1. That the stele, its fragments being found in Tel Dan, was, therefore, erected as a memorial over the victory of the king in (re)taking Dan.

2. That the Syrian king who erected the stele was very likely King Hazael of Damascus.

3. That the two kings he killed are very likely Jehoram of Israel and Ahaziah of Judah.

Other scholars, however, questions these conclusions. A. F. Rainey, e.g., thinks that the verbs for "kill" should be read as passive, "was killed"; this means that the text tells us nothing of who did the killing. S. Yamada argues that those same verbs really means "defeated," rather than "kill." J. W. Wesselius argues, on the other hand, that it was Jehu, rather than Hazael, who erected the stele.

Until more fragments of the stele are found, we will have to live with the uncertainties of the details of the inscriptions. The stele, however, puts paid to such nonsense as once used to be peddled around that such characters as David and Solomon were nothing more than fictitious figures conjured up by Yahweh worshippers to make up their propaganda.

Low Chai Hok

©Alberith, 2016