Exo 20:8-11 - "Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy. 9Six days you shall labor and do all your work, 10but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, neither you, nor your son or daughter, nor your manservant or maidservant, nor your animals, nor the alien within your gates. 11For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but he rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.

Deut 5:12-15 - "Observe the Sabbath day by keeping it holy, as the Lord your God has commanded you. 13Six days you shall labor and do all your work, 14but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, neither you, nor your son or daughter, nor your manservant or maidservant, nor your ox, your donkey or any of your animals, nor the alien within your gates, so that your manservant and maidservant may rest, as you do. 15Remember that you were slaves in Egypt and that the Lord your God brought you out of there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Therefore the Lord your God has commanded you to observe the Sabbath day.

The Fourth, or Sabbath, Commandment is the longest in the Decalogue. It is also the one which differs most in the way it is stated in the books of Exo and Deut. These differences arise out of the differing historical circumstances in which they are stated. In Exo the Commandments are reported as the supstance of what God had recently revealed to Moses on the mountain. In Deuteronomy they are recalled as part of Moses' farewell speech on the eve of his death, in which he expounds the Commandments to the new generation of Israelites who would enter and conquer the land, explaining to them what the laws mean and urging them to keep them in faithfulness to Yahweh.

The commandment in Exo opens with "remember the Sabbath," implying that the Israelites were already aware of or familiar with the commandment. In fact they had already been instructed of the commandment some two weeks previous to their arrival at Mount Sinai (Exo 16:1ff).1 "Remember" is, therefore, an appropriate verb for re-introducing the commandment. Deut, on the other hand, opens with the verb shamor which, given the urgency so characteristic of Moses' addresses now recorded in the book, is better translated as "give heed to," or "pay attention to" rather than the rather laidback "observe" found in most English translations.

The Hebrew word that follows next — leqaddesho — may be understood as spelling out either the means by which the Sabbath is observed ("by keeping it holy" as in NIV) or, more likely, the intent of the commandment ("to keep it holy" as in KJV, RSV, NKJ, NASB).2 Life in the land may tempt Israel, as it tempts us, to ignore the Sabbath commandment as a mere symbolic option, especially when pressured by the demands of a crop to be harvested in the face of threatening weather, or a billionaire client to be entertained. Leqaddesho, however it is understood, reminds Israel that the commandment is not an option, but a decision to give to God and his commandments a higher priority than our own worries, the possibility of economic loss or, worse, our children's music/ballet teacher's schedule. Like the Tenth Commandment, this commandment is underlined by a summons to trust in Yahweh's gracious readiness to meet one's needs, that calls us to exchange the life of grab—of grasping what we can when we can that comes so naturally to all of us—for a life of faith, of trusting in the provision of a God who, as Exodus and Deuteronomy keep insisting, knows what we need and when we will need them.

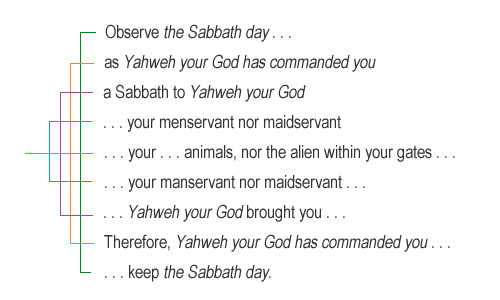

The next verses (vv9-10 in Exo, vv13-14 in Deut) define the Sabbath as a day of rest after six days of labour. The list of recipients upon whom Israel is commanded to exercise the gift of rest on the Sabbath (v14) is the most extended of any commandment found in the Old Testament. The laboured-ness of the specifics (7 in Exo and 9 in Deut) is puzzling, but seems to be an idiomatic expression intended to stress the breadth of its application rather than delineating who might or might not participate in the blessing of the Sabbath rest. This helps to explain the strange omission of wives from, and the inclusion of beasts of burden in, the list. For the second time in both books, though concerning different things, a command is recalled that includes the 'alien' in its ambit.3 The ger, 'alien' in the Old Testament describes any person who lives among people who are not his blood relatives and is, therefore, dependent on the grace of their hospitality. Any rights the alien enjoys he does so at the largesse of his host community. Here the command to Israel to secure this largesse not just for the ger who has no right to it, but also for the servants — those who cannot easily afford it — is underlined by setting both groups at the centre of the structure that frames the commandment:4

Whatever else happens on the other six days, on the seventh day every living creature in Israel enjoys the equality of rest, moments that constitute windows through which the light of hope shines. This commandment challenges us, who are surrounded everywhere by multitudes of migrant workers and economically disadvantaged in a globalized economy, even as it resonates with Jesus's offer of rest to all who are weary and burdened and his command to love our neighbours as ourselves (Mt 11:28; 19:19). We built a new home during the course of writing this commentary. While drawing up the plans we were asked where we wanted the servant's room. This commandment defied my wife and I to ask if we are not responsible to provide servants—should we have them, that is—with living quarters as decent as those we plan for ourselves, instead of sequestering them in some tiny cubicle next to the storeroom, with the neighbour's septic tank for a view, which is such an Asian thing to do.5 We also cannot see that the commandment avails the clever option that the servants may be waived their rest one day in seven in lieu of monetary supstitute. We now ask, in our home, all our visitors who bring along their servants that they sit and eat together at the same table; we think it a wonderful act of anticipation of the Grand Banquet where all our joys and hopes (of rest, equality and dignity) will be made complete, a grand denouement of which every meal and, more particularly, every Sabbath is only a faint prelude.

The commandment in Exo ends with what is often understood as the "reason" for the commandment: "For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but he rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy" (v11). This clearly harks back to the so-called "creation account" in Gen 1:1-2:3, and particularly 2:2-3. Another way of understanding the verse is to see it not so much as the reason, but as a "motivational clause" for Israel to do likewise. What is offered here, then, is the ultimate gift of aspiration — to be like God! Israel can be like God, simply by resting on the seventh day, blessing it and making it holy as a result.

This reason is omitted in Deut which, instead, concludes with a reminder to Israel that they were slaves in Egypt but had been delivered by Yahweh as the reason for Yahweh' command to observe the Sabbath. It has often been claimed that this difference arose out of the different perspectives of the different theological traditions from which the authors composed the two books, that Exo reflects a "creational perspective" while Deut reflects a humanitarian concern (i.e., because Israel knows what it means to be ill-treated, she should now treat others well). The logic underlining the proposal is specious.6 The recall of Israel's past as slaves as motive for observing the Sabbath only explains why Israel should treat others well — here by extending the gift of rest on the Sabbath day to those who cannot enable it for themselves; it cannot, however, explain why one day in seven should be hallowed. The commandment instructs Israel to observe the Sabbath leqaddesho. This sanctity finds its explanation in the fact that it was to be "a Sabbath to Yahweh" (v14), an explanation that is rooted in the so-called creational perspective of Exo but assumed by Deut. The teaching of Deut represents Moses' matured reflection of a lifetime of leading and pastoring two genereations of Israelites. In the course of such reflection, the deep sense of thankful rememberance of Yahweh's gracious provisions in and since the days of Egypt often drives Moses to call Israel to acts of faith on the basis of such rememberances, as illustrated in the following examples:

"Remember the day you stood before the Lord your God at Horeb, when he . . . Therefore watch yourselves very carefully, o that you do not become corrupt and make for yourselves an idol, an image of any shape . . . " (Deut 4:10-16)

"But do not be afraid of them; remember well what the Lord your God did to Pharaoh and to all Egypt. You saw with your own eyes the great trials, the miraculous signs and wonders, the mighty hand and outstretched arm, with which the Lord your God brought you out. The Lord your God will do the same to all the peoples you now fear . . . Do not be terrified by them, for the Lord your God, who is among you, is a great and awesome God. (Deut 7:18-21)

There will always be poor people in the land. Therefore I command you to be openhanded toward your brothers and toward the poor and needy in your land. If a fellow Hebrew, a man or a woman, sells himself to you and serves you six years, in the seventh year you must let him go free. And when you release him, do not send him away empty-handed. Supply him liberally from your flock, your threshing floor and your winepress. Give to him as the Lord your God has blessed you. Remember that you were slaves in Egypt and the Lord your God redeemed you. That is why I give you this command today. (Deut 15:1)

Do not deprive the alien or the fatherless of justice, or take the cloak of the widow as a pledge. Remember that you were slaves in Egypt and the Lord your God redeemed you from there. That is why I command you to do this. (Deut 24:17-18)

When you are harvesting in your field and you overlook a sheaf, do not go back to get it. Leave it for the alien, the fatherless and the widow, so that the Lord your God may bless you in all the work of your hands. When you beat the olives from your trees, do not go over the branches a second time. Leave what remains for the alien, the fatherless and the widow. When you harvest the grapes in your vineyard, do not go over the vines again. Leave what remains for the alien, the fatherless and the widow. Remember that you were slaves in Egypt. That is why I command you to do this. (Deut 24:19-22)

For Moses, there is no true Sabbath rest, no true remembrance of God's grace and provisions and all that they imply for us if we do not also extend those blessings and privileges to all those to whom it is in our power to do so. God worked six days and rested on the seventh. He extends that to us by commanding us to work six days and rest on the seventh. We are, therefore, missing something very fundamental to our gospel if we do not then make it possible for those in our care and power to have to work only six days and rest on the seventh.7

You may wish to read the following article: Sabbath

Low Chai Hok

©Alberith, 2013