The Ten Commandments, or Decalogue, are the most well known feature of the Judeo-Christian faith, more so than even the Sermon on the Mount. And well-known enough to elicit all sorts of copy-cat declarations, of which "The Hutu Ten Commandments," with its explicit promotion of genocidal hatred, must surely qualify as the most perverse; its Eighth Commandment—probably the most often quoted in Rwanda in the early 1990's, just prior to the murder of a million Tutsis in just one hundred days—said, "Hutus must stop having mercy on the Tutsis."1 Despite such familiarity, there remains disagreement on how the original should be enumerated. In many Christian traditions, "I am Yahweh your God who brought you out of Egypt . . . you shall have no other gods before me" is the First Commandment, and "you shall not make for yourself and image . . ." makes up the Second Commandment. Roman Catholics and Lutherans, however, run these two together into a single commandment but divide the commandment not to "covet your neighbour's wife" and the command not to "set your desire on your neighbour's house . . ." into the Ninth and the Tenth Commandment respectively.2

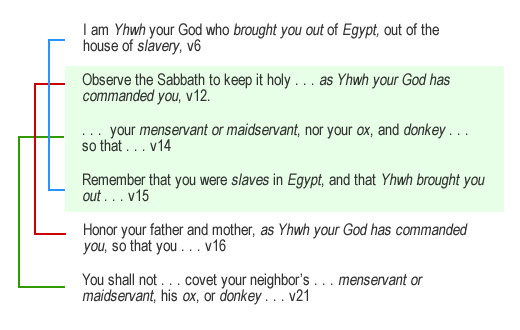

Though we know that the Decalogue was originally inscribed on two tablets, we also do not know what went on each of them. Tradition, however, places those that enjoin duties to God (usually identified as the first four) on the first tablet, and those that relate Israel one to another (the last six) on the second. Despite its catechetical advantage, such a division—and even the basis of the division—should not be pressed too strongly.3 For, in a manner that is not evident in its presentation in Exo.20:8-11, the Sabbath commandment is presented in Deut 5:12-15 as a bridge between acknowledging Yahweh as Lord and living right by our parents and neighbours, so that all the commandments of the so-called Second Tablet issues from and coheres in the opening invocation of Yahweh as the giver of the commandments:

Taken together the first three commandments (vv6-11) constitute a call to radicalize the lordship of Yahweh. The fourth—the Sabbath commandment—as it is formulated in Deuteronomy, calls Israel to a communal affirmation of God's providential grace by giving rest to those whose yoke are heavy. Coveting—against which the last commandment forbids—is, fundamentally, the most socially damaging manifestation of discontent, a distrust in God's gracious readiness to meet one's needs. These two commandments thus frame the last seven commandments which, taken together, call Israel to radicalize their responsibility and commitment towards one another.

In this way, Deuteronomy ties Israel's ethics explicitly into what it affirms about Yahweh's character and his prior actions on her behalf. Consistent with this, we note that, whatever similarities they might bear to extra-biblical law codes and however we see the laws (especially the Sixth to the Tenth Commandments) as "natural laws," as Calvin, Scotus and some of the church fathers did4, the Ten Commandments are Yahweh's laws. What this means is that Israel's ethics is always theologically predicated; the decisions the people of God make they make because of who God is and what He has commanded, and because of whom they are to Him. Whether gains the obedience to the commandments may bring is quite simply beside the point; the commandments are to be obeyed because they have been commanded.

Thus, the Ten Commandments were given absolutely. In contrast to many of the casuistic laws found elsewhere in Deuteronomy, there are no situations where what is commanded in the Decalogue may be waived. Now, it has often been noted that the Decalogue are not particularly "religious" in orientation—they are addressed to the individual Israelite within the context of the home and neighbourhood ("you," 2nd. per. sg.). This makes their obedience a matter of personal responsibility for everyone, but also brings all realms of life under the lordship of Yahweh. This has the effect, interestingly, of underlining the Decalogue's authority in the life of Israel, and in ours.

Different views have been given regarding whether Christians, living under the New Covenant, are required to observe the Decalogue. One popular view is to say "No" because it given within the context of the Old Covenant established between Yahweh and ancient Israel. The Christian's relationship with God is established on the basis of the vicarious death of Christ on the Cross. As it stands the arugment cannot be faulted. The arguement, however, is incomplete, because it fails to recognize that, though the Commandments (especially) were given within the context of the Old Covenant, they express the will of Yahweh concerning issues that are of universal significance and that reflect the fundamental character of God in a way that most of the other OT requirements do not. Does any one taking that argument want to say that Christians, being free of the Old Covenent requirements, may now "have other gods before Him," or to "make for yourself an idol . . . and to bow down to them or worship them"? Surely not! Surely it cannot be the case that Christians may now "misuse the name of Yahweh," or to steal or commit murder! Of course, it may be argued, all of these requirements are, in one way or another, reaffirmed in the NT, which makes them normative. If that is the case, that it simply affirms what we are saying about the weaknesses of the popular argument noted above, as well as to affirm that the Decalogue are to be obeyed.

The Ten Commandments were given to be kept. But what does keeping the Ten Commandments do for us? Much. Since they are the fundamental expressions of God's holy character, keeping them — beyond bringing order to society — will inculcate in us a moral-ethical mindset like God's. That will take us one step back to God's original plan for us when he made us "in his image." Yet viewed against the larger picture of God's salvific economy, keeping the commandments will not count for much. To the ruler who asked Jesus what he needed to do to inherit eternal life, having already observed all the Ten Commandments since he was a boy, Jesus told him, "You still lack one thing. Sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me" (Lk 18:22) The ruler went away very sad. Obeying the Ten Commandments, according to Jesus, accomplishes nothing if it is not accompanied by a commitment to love and follow Him at all cost. From a Christian perspective, then, the essence of all ten commandments, and the key to fulfilling their obedience, is to be found in Paul's great declaration that—for to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain" (Phil.1:21).

Obeying the Ten Commandments,

according to Jesus,

accomplishes nothing

if it is not accompanied

by a commitment to

love and to follow Him at all cost.

You may be interested in the following resources:

Christopher J. H. Wright, "The Israelite Household and the Decalogue: The Social Background and Significance of Some Commandments," Tyndale Bulletin 30 (1979): 101-124.

David L. Baker,"The Finger of God and the Forming of a Nation: The Origin and Purpose of the Decalogue," Tyndale Bulletin 56.1 (2005): 1-24.

D. L. Baker, "Ten Commandments, Two Tablets: The Shape of the Decalogue," Themelios 30.3 (2005): 6-22.

Low Chai Hok

©Alberith, 2017