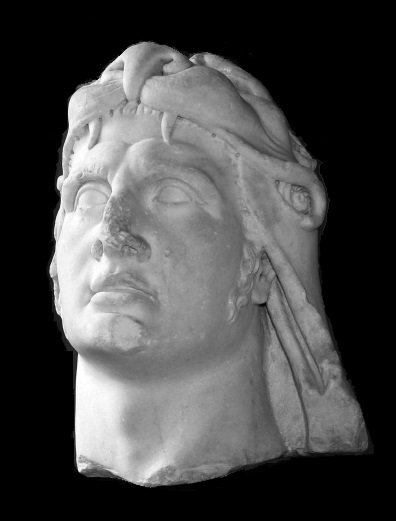

Though not mentioned in the Bible, Mithridates is a man you quickly encounter when you read in the historical backgrounds pertinent to it. King of Pontus (a former satrapy of the Persian empire on the Black Sea coast, in what is now northern Turkey) from 120 BC onwards, Mithridates was famous as one Rome's most formidable and tenacious enemies, waging three long wars against Roman forces in the east, until he was finally defeated by Pompey in 66 BC (from whence Pompey continued on to the East and forced a settlement in Judea in 63 BC which effectively handed power to the Herodian family).

Mithridates had a notorious childhood. Persecuted by his mother, he ran off and survived on any way he could in the forest. Worried that his mother might still try to poison him, he learned all he knew about poisons and took doses of it everyday to make himself immune to them. When his father was assassinated in 120 BC, he returned to claim his throne when he also killed his mother and, for good measure, also his brothers and sisters (except one who became one of several wives he later married).

His father, Mithridates V, had been a friend of Rome prior to this death. In 133 BC the last king of Pergamun, Attalus III, had died but had willed his kingdom to the Roman senate. Attalus's half-brother, however, tried to claim the kingdom for himself. At that time Mithridates senior had come to the aid of the Romans in their war against the would-be usurper and was, afterwards, awarded part of the territory of Phrygia. When he died and Mithridates VI came to the throne, however, the Romans went back on their pledge and took back the Phrygian territory. That, naturally soured the relationship for the young king. Recognizing that he could not interfere in the west in which the Romans had an interest, or yet strong enough to take them on, he was able, nonetheless, to extend his power eastward both in conquests and diplomatic arrangements, which included the now disintegrating Seleucid empire. In time he became the most powerful ruler in Asia, and ready to take on Rome.

The initial provocation to war came from the Romans and Roman generals vied for the honour to bring him to heel (Marius and Sulla risked civil war over the commission to fight Mithridates). It took three major wars until Pompey was charged to deal with him once and for all, when he was defeated in Mithridates was finally defeated in 66 BC. Mithridates fled Pontus for Armenia where his son-in-law, however, refused him entry. He made for his remaining territories in the Crimea in 65. There he made a last attempt to raise an army to take the fight to the enemy's gate, to attack Rome by invading the Italian peninsula. His son, Phanaces, however, betrayed him by raising an mutiny in the army. Sick and old, Mithridates had had enough. In 63, he decided he would kill himself by taking poison. Two of his daughters would not permit him to do so unless they too were allowed to join him in a suicide pact. They died quickly. He, immune to them, took so long he finally commanded his guard to kill him, so that the Romans will not get to parade him as a vanquished. His treacherous son, however, surrendered his body to Pompey. Recognizing that "the status of the conqueror was commensurate with the status of the defeated," Pompey hailed Mithridates as the greatest king of his day, and gave him an honourable burial. Pharnaces II, his son who inherited his kingdom would one day again have to do battle with Rome, in the person of Julius Caesar (from which the latter emerged to proclaim, "I came, I saw, I conquer.")

Adrienne Mayor, The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Tom Holland, Rubicon. The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic. London: Abacus, 2003.

©ALBERITH